A Quick Plug for My Book

Hello. Thank you for clicking on this link, and I hope you enjoy this essay. Writing a book was the genesis of my blogging and becoming a video content creator. I have published part one of my book project entitled, The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story. It is currently available on Amazon in eBook, hardcover, and paperback formats. Shortly I will be selling signed hardcover and paperback copies on my online store entitled Big Words Authors. You can place an order now if you want a signed copy. The paperback edition is also available on IngramSpark. There is also a page discussing the book. Please consider visiting it to learn more about the project and see promotional content I’ve created surrounding the project. And now on to our feature presentation.

Another Promotional Essay For The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story

This essay is another promotional piece for my two-part book project entitled, The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story. To learn more about the project, visit the overview page I created for it here on Big Words Authors. As described in earlier pieces I’ve created surrounding book, I’ve conducted considerable research for this project. A part of this research involved interviewing 30-40 players and coaches from Section VI, and from my era. For those unfamiliar, Section VI is the New York State Public High School Athletic Association’s (NYPHSAA’s) western-most section, encompassing the counties of Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, Erie, Niagara, and Orleans.

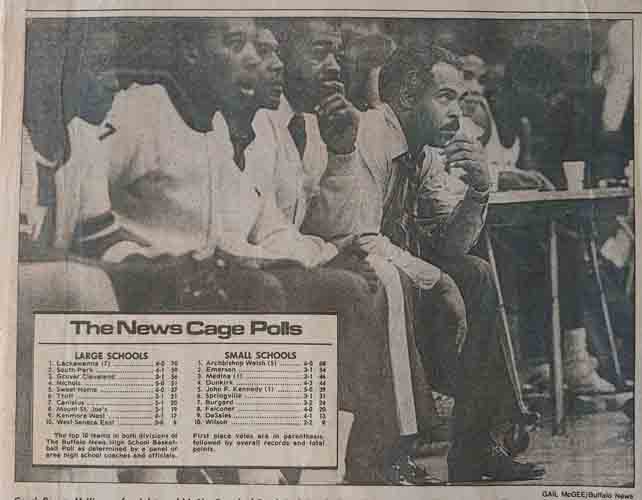

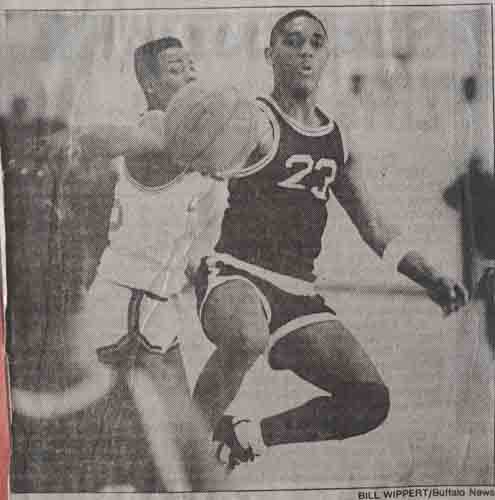

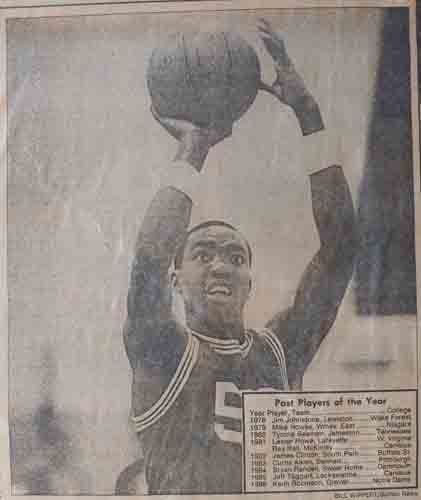

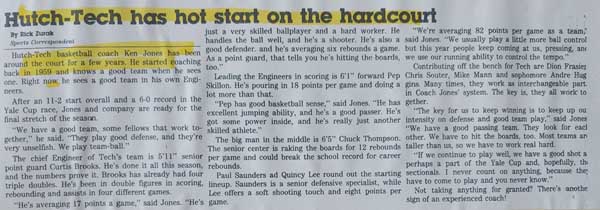

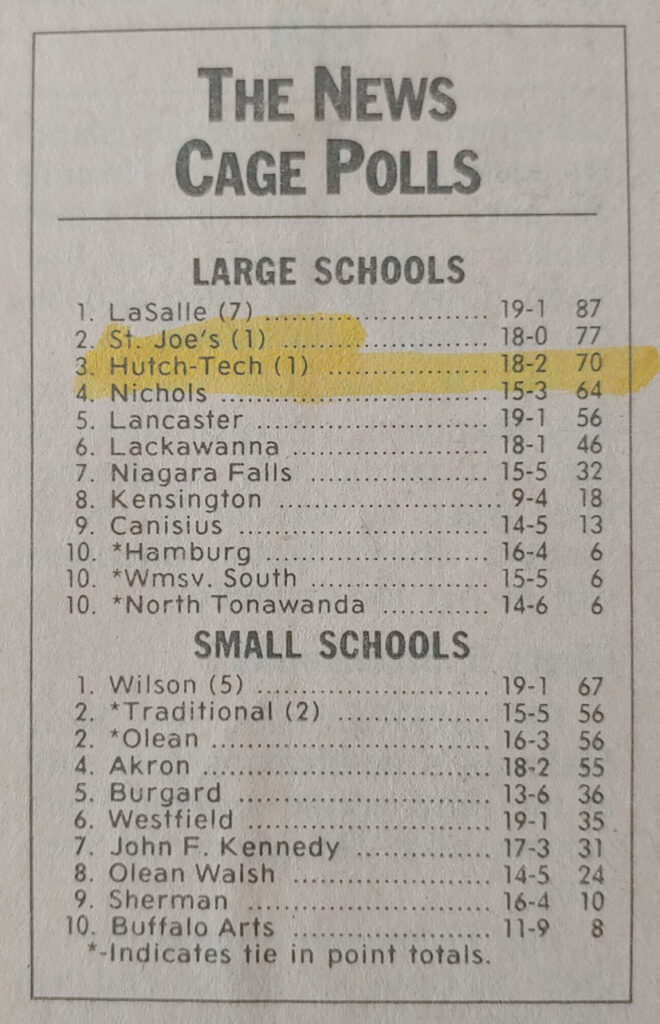

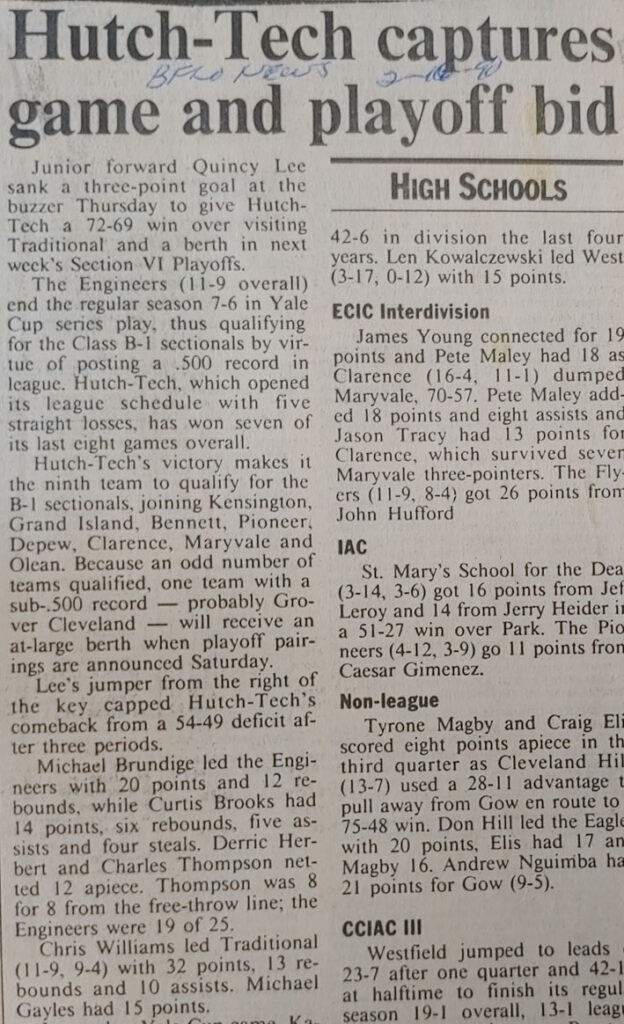

Some of the pictures used in this essay come from an archive of Section VI basketball. It was assembled over the years from issues of the Buffalo News by my first Coach at Hutch-Tech High School, Dr. Kenneth Leon Jones. Other pictures were taken from yearbooks from Hutch-Tech High School from the early 1990s. Coach Jones is discussed throughout this piece and is hyperlinked to a previous essay. Finally, a video about him from my sports YouTube channel is embedded at the end of this essay.

The Story Of The 1990-91 Hutch-Tech Boys’ Varsity Basketball Team

“That was a great feeling being around a group of guys who played together and really liked being around each other!”

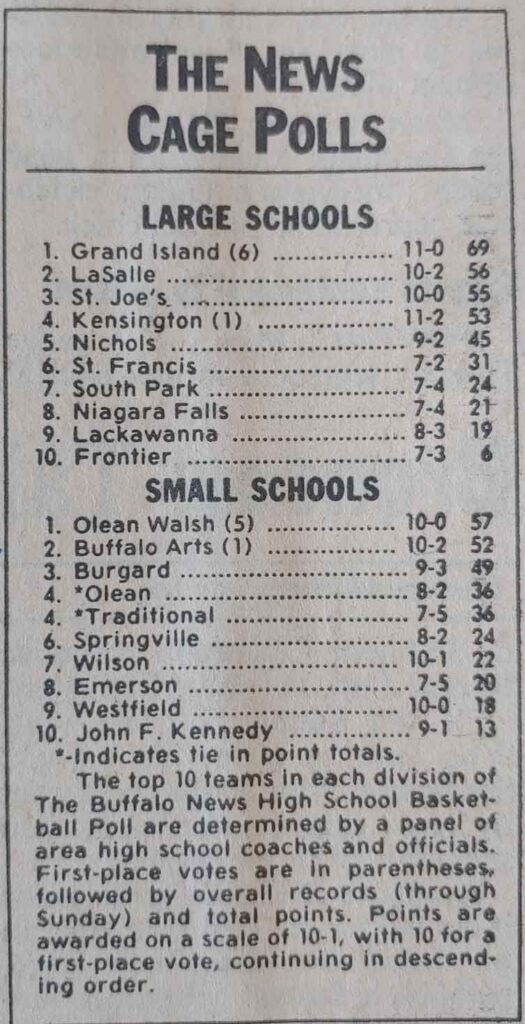

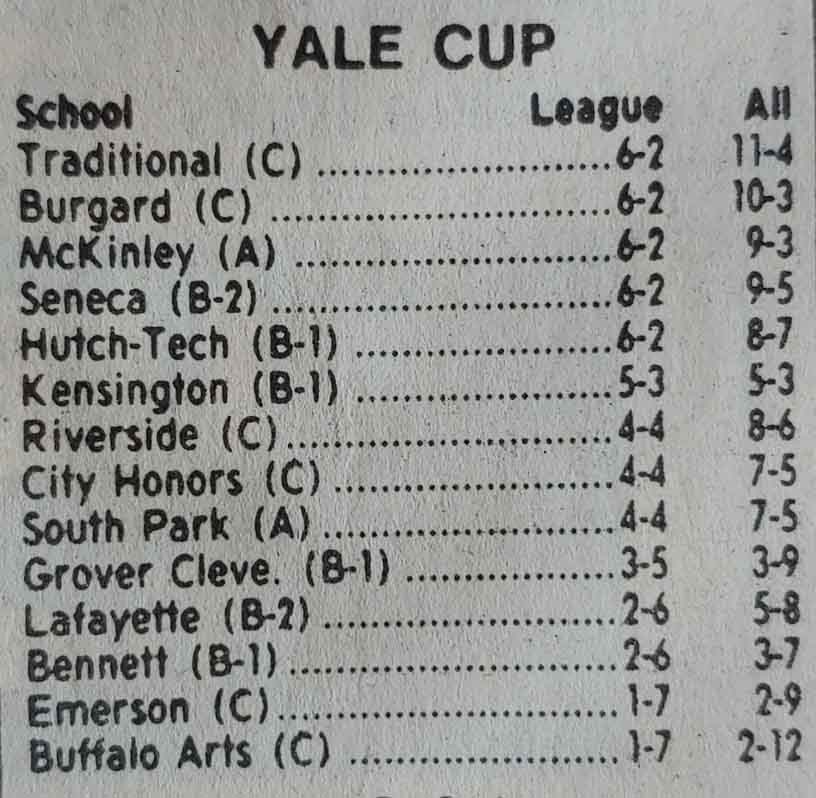

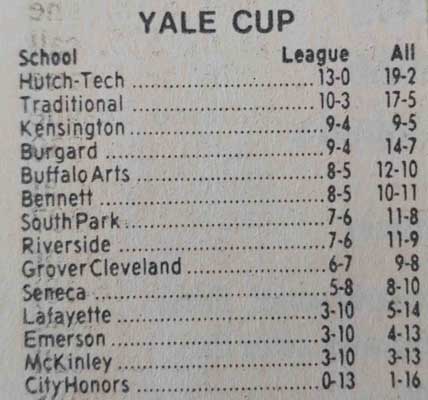

During my freshman year at Hutch-Tech High School, the 1990-91 Engineers went on a magical run winning our city league, the “Yale Cup” with a record of 13-0. They then marched through the Section VI Class B playoff bracket to win that championship. Their season ended one game short of a berth in the State Final Four in Glens Falls, NY, which I’ll discuss later. From my vantage point at the time, it was a very big deal. Afterwards I dreamt of doing what they did.

Interestingly, my research revealed multiple points of view on that magical season. It also revealed the significance of the 1990-91 team’s accomplishments relative to those of other Section VI teams of that era. In my book project, there is an entire bonus chapter dedicated to the 1990-91 Engineers. However, I also wanted to create a promotional/teaser piece just dedicated to them.

We Didn’t Do Anything That Spectacular! A Perspective On The Story

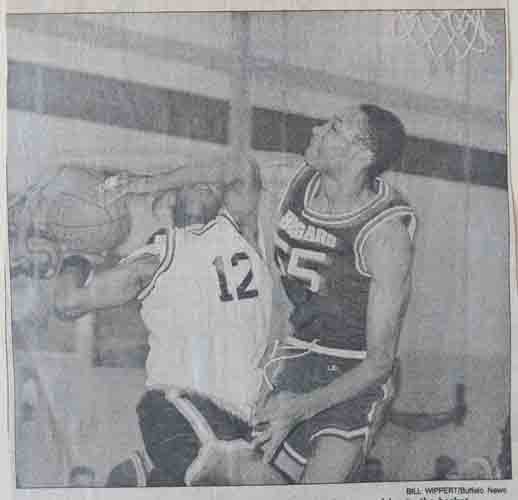

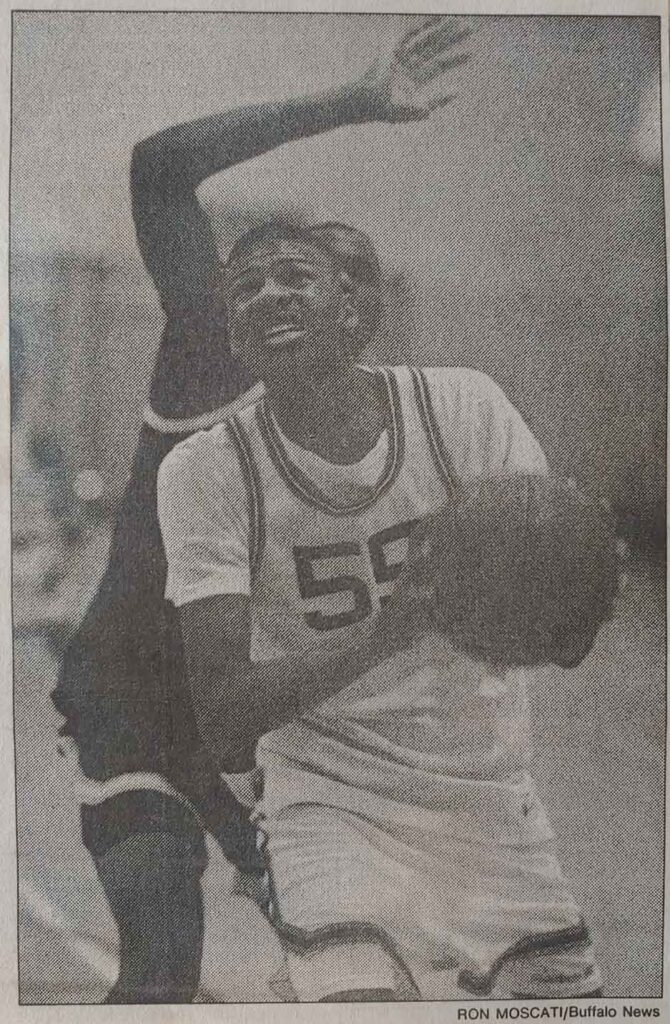

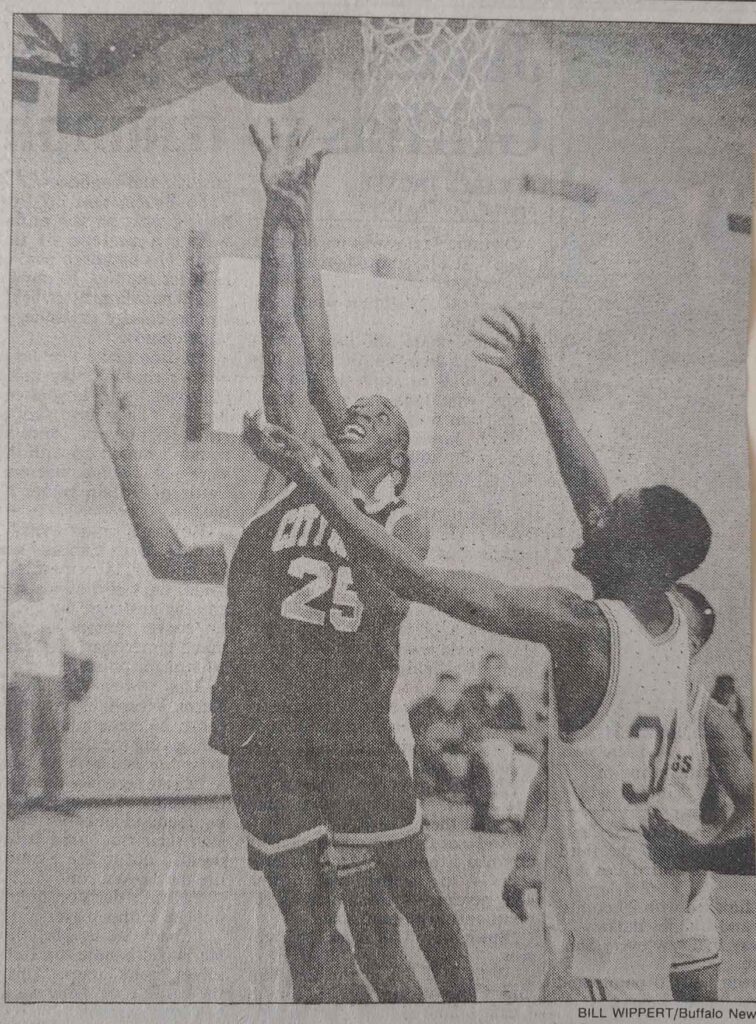

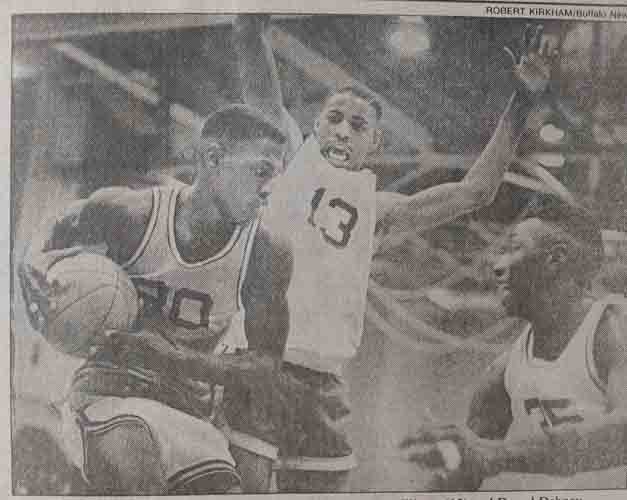

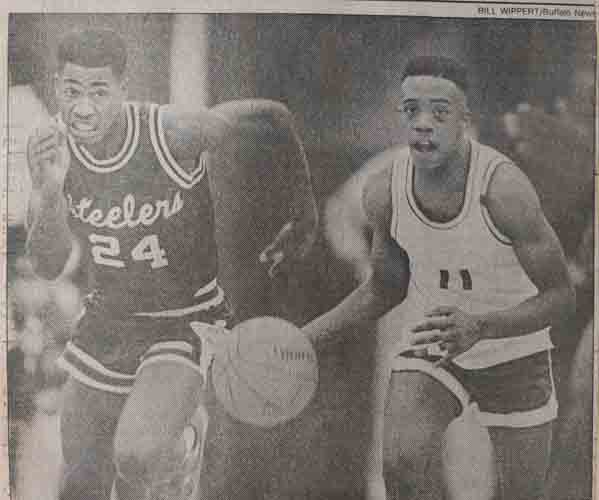

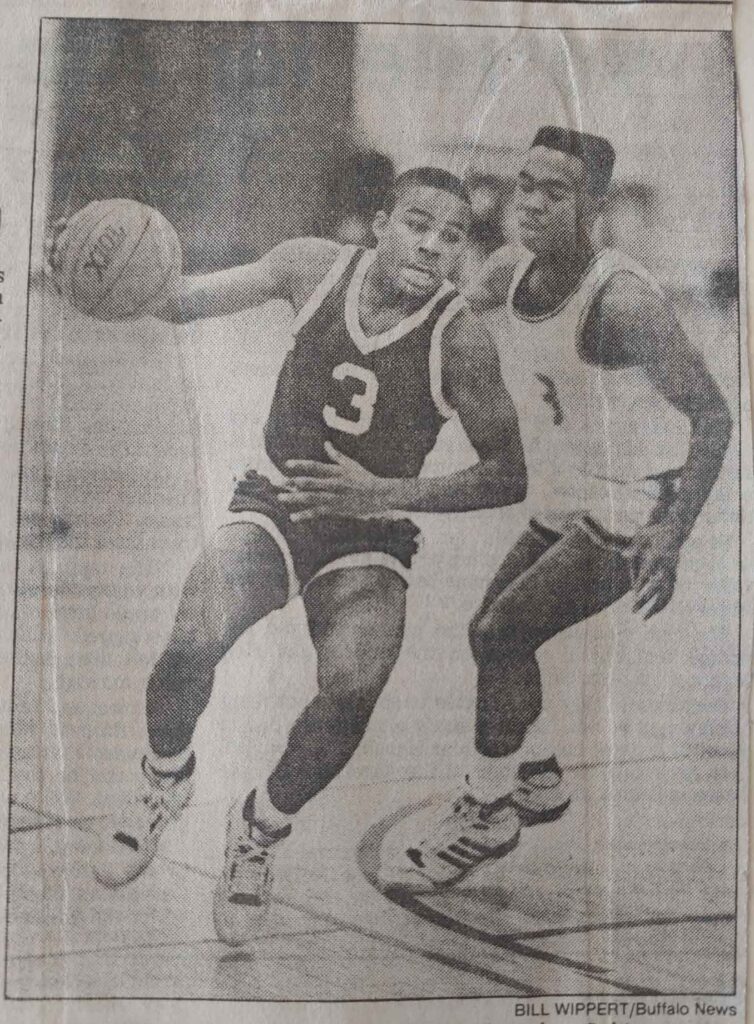

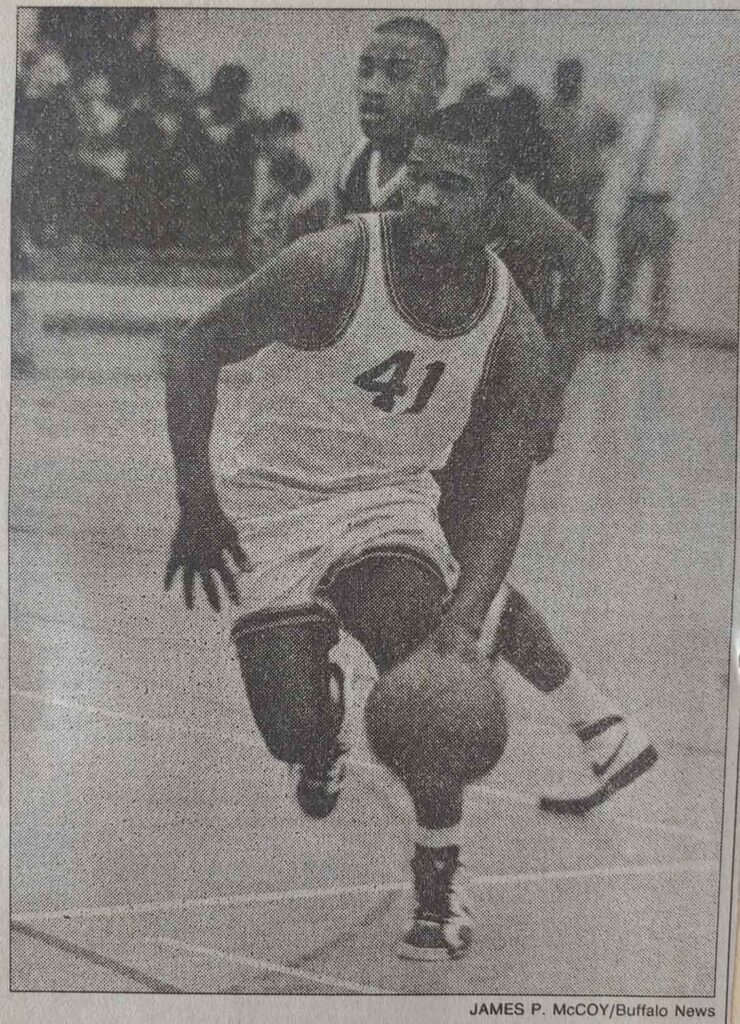

“When I heard you wanted to interview me, I was thinking, ‘Man, we weren’t a special team. We didn’t do anything that spectacular,’” said No. 13, Curtis Brooks (pictured above guarding Mike Mitchell of Williamsville South High School). He was the starting point guard and one of the leaders of the 1990-91 team. It was a summer-fall day when I interviewed him in downtown Washington, DC at L’ Enfant Plaza. We sat outside at lunch time, and you could hear the flurry of government workers and contractors walking by as well as the commuter trains coming and going in the background.

One of the most exciting interviews for me was that with No. 13. In The Engineers, I describe him as the ‘engine’ that drove the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team during its magical season. Interestingly, while I looked back at Brooks, his teammates, and their accomplishments with reverence, he surprisingly wondered what they had done that was so special.

Keep in mind that we were both in our 40s at the time. We both travelled the country and had many experiences outside of Buffalo. Furthermore, in all honesty, when you think about high school state championships, NCAA championships and NBA world championships, how big a deal is it to win your city league and sectional championships in high school? In comparison to the former three accomplishments, maybe it isn’t that big a deal. However, for a freshman just coming into the school with little understanding of the game and its multiple contexts and layers, it was a very big deal.

We Still Don’t Know How Ya’ll Did That!

“We weren’t the most talented team, but we knew each other. What that team had been through with Jones (Coach Ken Jones), we were comfortable with the system, and everyone had gotten better. We had played together,” Jerrold “Pep” Skillon said regarding the 1990-91 team’s championship run. “To this day, some of the players from the other the Yale Cup teams still say, ‘We still don’t know how ya’ll did that!’” I laughed at this revelation by Skillon as I could imagine the disbelief of players from the other schools continuing years later. How did Hutch-Tech of all the 14 Yale Cup schools do that?

“We did have some good players but even if you were better talent-wise, we had better team chemistry! That goes back to what you were saying in terms of the teams you played on – they didn’t have that chemistry. It was like everybody for themselves,” Skillon continued contrasting his experience with mine. “Well, we didn’t have that! These were my boys. We all came up in high school together, and we hung out after games. We were boys (friends)!”

Going 13-0 In The Yale Cup

By the way, how common was it to go 13-0 in the Yale Cup? In some of our last talks, our late coach, Dr. Kenneth Leon Jones, a central character in my story, asked me to investigate who had done it before his beloved 1990-91 team. Approximately four years earlier, the Trevor Ruffin-led Bennett “Tigers” did it on their way to the State Class B Final Four in Glens Falls, NY.

I believe the Buffalo Traditional Bulls, led by Damien Foster and Jason Rowe, did it in their magical senior seasons in 1995-96 (all their seasons were magical in my opinion). It also turns out that Hutch-Tech had done it back in the 1970s. Someone on Facebook who commented an earlier Engineers team had done it when I shared the overview page for The Engineers in the group, “You know you’re from Buffalo, NY if……”. Regardless, it was a head-scratcher for many at the time that the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team got it done in the fashion they did.

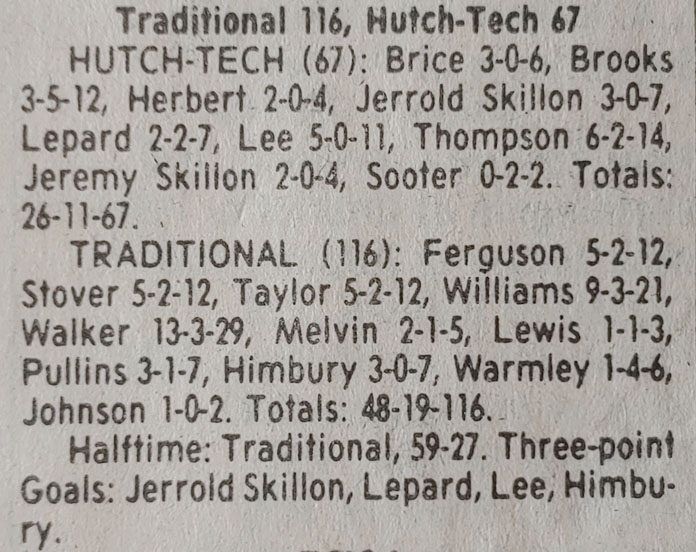

Losing To Buffalo Traditional By 49 And Marcus Whitfield Scoring 50 Points

“I’m not going to lie and say that I wasn’t embarrassed. I remember to this day, the Traditional game sophomore year. They beat us by 49 points. I never lost a game like that game in my life! We were embarrassed. My cousin went there, and Traditional had a bunch of pretty girls,” Pep Skillon said reflecting on a lopsided loss to Buffalo Traditional his sophomore year, Coach Jones’ first year. “We go in there and everybody’s got their hair cut, all that. We got stomped!

“Don’t get me wrong, they were one of the best teams in the area at the time. They went on a run to the states that year, whatever, but I remember that. They stomped us. I’ll never forget that game, they stomped us out. That was an embarrassing game sophomore year.”

“Marcus Whitfield, he scored 50 points on us! We were losing but we were like, ‘He’s not going to get 50 on us,’ but then he got 50 on the nose. We did have some pride, but we didn’t have the horses,” Skillon continued. “I remember that Burgard game where they blew us out because he scored 50 and the Traditional game. Those games stood out because that was the first time, I was embarrassed on the basketball court. We didn’t fight hard. Traditional beat us by 49 points and he put up 50 points again us (Whitfield).”

Experiencing Sobering Losses Early On: Iron Sharpening Iron

“I think we went 3-15. It was miserable in the sense that you never want to be part of a losing team. That was the year – I played against Ritchie Campbell, Marcus Whitfield – we played Burgard at home that year and I think we lost by 60 points (laughing),” said Reverend Dion Frasier of his freshman season. “Man, these cats – Ritchie was throwing the ball off the backboard and ‘Ice Cream’ was catching it and dunking it.

“They KILLED us! Ice Cream was Marcus Whitfield. They waxed us but that was a memorable game for me because that was the first time, I ever played in a varsity game. I got in the game because we were getting blown out and that’s when I scored my first two points. It was miserable, but it was fun!”

These two excerpts from my discussions with Pep Skillon and Dion Frasier, were fun to listen to and educational as well. The core players of the 1990-91 Engineers not only grew up in Coach Jones’ system together, but they also experienced several difficult losses early on which helped galvanize them as a team. Furthermore, they got experience playing against some of the Yale Cup’s all-time greats including Ritchie Campbell and Marcus Whitfield. I’d heard about the legend of Ritchie Campbell before, but this was my first time hearing about Marcus Whitfield’s brilliance.

The “Risk Factor”: A Key Ingredient To The 1990-91 Team’s Success

There were several keys to the 1990-91 Engineers’ magical season. One was the hands-on experience against some of the area’s greatest players just described. The term “The Risk Factor” came also back to me as I was writing this essay. Coach Jones shared the term with me when we discussed his beloved 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team. As I’ll describe, it involved one of his key basketball teachings, disciplined ‘man to man’ team defense.

“We were small,” said Reverend Dion Frasier reflecting on the 1990-91 season, his junior year. The 1990-91 Engineers weren’t the biggest or most physically talented team that ever took the floor in the Yale Cup. A part of their secret to success though was the disciplined and staunch man to man team defense that they played, particularly their backcourt.

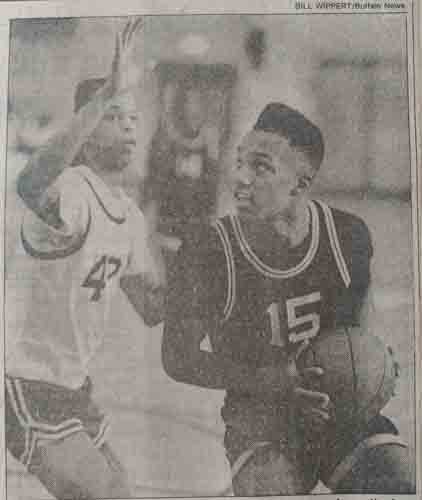

In addition to the above-mentioned No. 13, Curtis Brooks, there was also No. 40, Paul Saunders. Neither guard was taller than 6’2”, but they were stellar defenders. In fact, Coach Jones attributed the team’s success in large part to No. 13’s and No. 40’s defensive tenacity. Their long arms and quick feet allowed them to take ‘risks’ or anticipate/gamble for steals. Likewise, they recovered easily whenever they anticipated incorrectly. Their play created lots of easy baskets for the team, a key ingredient to its success that season. This was one of the ways they were able to score 100 points or more multiple times that season (or close to it).

Was It The Chemistry?

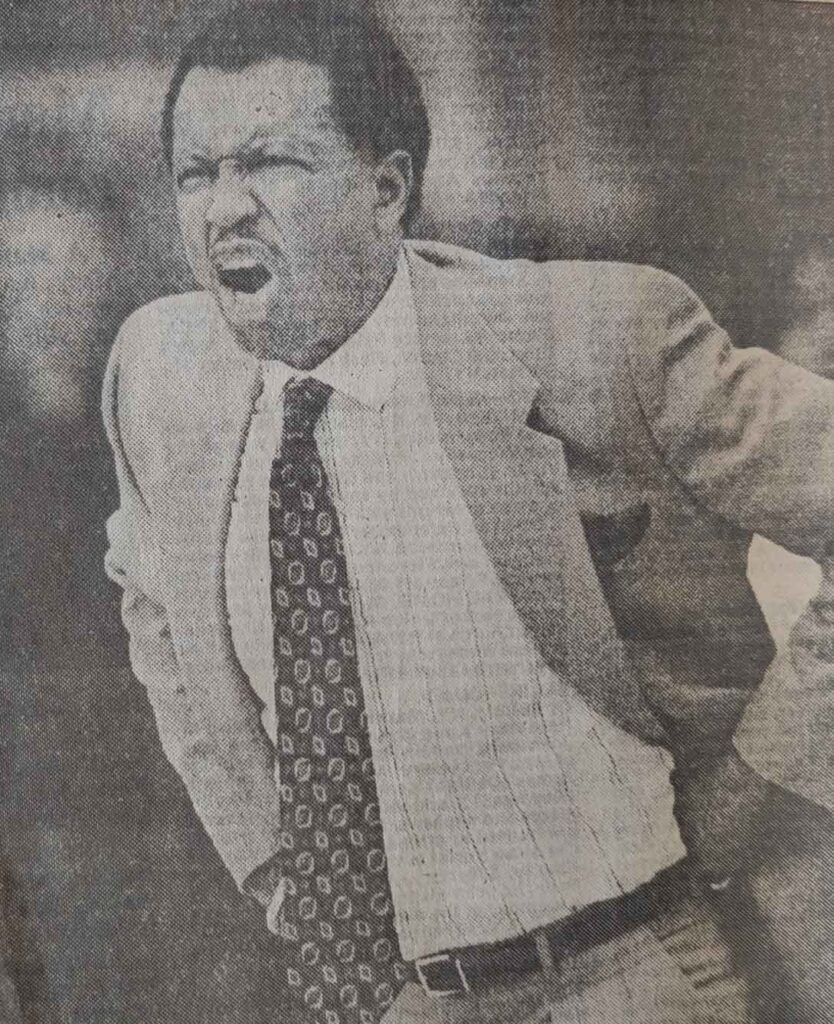

“It was the chemistry that made that team successful, NOT the coaching!” Most of the content I’ve created surrounding my project has lauded Coach Ken Jones. In fact, there are many of us who still look back on him with gratitude and reverence. That said, as described in my piece entitled, Lasting Lessons Basketball Taught Me: Different Things To Different People, he did have his share of detractors and critics. Some of them sat on the bench with him wearing the maroon gold Hutch-Tech uniforms. To learn some more about Coach Jones and his legacy, once again see the embedded video at the end of this essay.

The last quote regarding the team’s chemistry came from a player whom most of us knew around school as ‘J-Bird’. J-Bird was No. 34 Jermaine Skillon, the younger brother of the above-mentioned Pep Skillon. His was another one of my favorite interviews due to the levity in our discussion. J-Bird was yet another talented player on the 1990-91 team, and he was from my brother’s and the above-mentioned Dion Frasier’s Class of 1992. Let’s just say that J-Bird didn’t always see eye to eye with Coach Jones. Looking back, he believed it was the chemistry amongst the core of the 1990-91 team that led to its success that season and not the coaching per se.

I’ve shared this not to stir controversy, but to note that for a given piece of history, there are often multiple points of view, and I think J-Bird’s is worth considering. I experienced the importance of team chemistry during my short basketball journey, and what happens when you don’t have it. It’s also something I’ve witnessed play out in sports as a spectator years after high school. This spans across all levels: high school, college, the pros and even in the Olympics. It even plays a role in work settings.

Playing Both Yale Cup And Fundamental Basketball

“On defense you ANTICIPATE, and on offense you REACT!” This was one of Coach Jones’ most fundamental teachings. Other players in fact attributed the 1990-91 team’s success to Coach Jones’ fundamentals, principles, and his system. As described in many of my writings and videos, Coach Jones’ hallmark teachings were fundamentals, team defense, and both disciplined and unselfishness on offense. He encouraged taking good shots on offense and ‘working’ the ball for uncontested layups. Having played under him for a brief period, and after conducting my many interviews, my conclusion is that the 1990-91 team’s success was a mixture of both the team’s chemistry and Coach Jones’ system.

J-Bird’s brother, Pep, acknowledged that the 1990-91 Engineers were equipped to play multiple styles of basketball. They could play a more ‘up and down’, ‘racehorse’ style of game that the Yale Cup was known for. They were also trained to play the slower more disciplined suburban-style which involved set offenses, often to counter zone defenses. Many Yale Cup teams played zone defenses to prevent penetration and to avoid individual players getting into foul trouble. Many of the suburban teams also played zone, but for the purpose of countering the more athletic style played by most Yale Cup schools.

When necessary, the 1990-91 Engineers were trained to methodically ‘work’ the ball to find good shots for the team. They routinely did this instead of hoisting up the first available shot or driving to the basket with ‘reckless abandon’ as they say. Working the ball was a term Coach Jones used for patiently finding quality shots on offense, and not taking a shot early in a possession if unnecessary. Likewise, many of the suburban teams were astonished to see a Yale Cup school play this way as it was out of character for our league.

More On Chemistry, Competitive Will And Killer Instinct

Again, the chemistry was critical too. If you look throughout sports, the players on most championship teams enjoy being around one another. They often hang out together in their spare time. They unselfishly accept their roles within the unit even if it means not being in the spotlight. If certain players within the team are struggling, the others have a way of encouraging them. Carlos Bradberry, of the LaSalle Explorers, noted this in my interview with him regarding team chemistry.

“Curt Brooks was a warrior! He was at the park every day in the summer before our senior year practicing in a weight jacket,” said another senior from the 1990-91 team, No. 11, Quincy Lee. Brooks was humble about this as well when I asked him about it. It was something he did for a competitive edge and to make up for the hours he spent at his job that summer of 1990, and away from the basketball court.

This is significant because as I learned in my own basketball journey, regardless of how thorough a coach’s system is, it can’t completely cover up a lack of talent and ability, bad team chemistry and a lack of camaraderie. It can sometimes cover up for injuries and having lesser talent. It also can’t give players a sense of drive, killer instinct, or passion. The core of the 1990-91 team had these qualities.

The “Mighty” Hutch-Tech

“On the news at nighttime they called us ‘The MIGHTY Hutch-Tech’!” I was a freshman that 1990-91 season so I didn’t witness all the fanfare surrounding the team. A low grade in one class prevented me from participating in the program early that season as their momentum gradually built. I just watched a few games from the sidelines and listened to the morning announcements, not understanding the significance of everything. The above-mentioned Quincy Lee, one of the seniors on that team shared with me during our interview that one of the news stations gave them a special nickname as they continued winning that season.

“I can’t believe they had us ranked third in the state,” Coach Jones said in my first year on the team (the 1991-92 season) and then years later. After two early season losses to the Willie Cauley-led Niagara Falls Senior High School “Power Cats”, they went on a 17-game winning streak, during which it seemed they couldn’t lose again. That winning streak included going 13-0 in the Yale Cup. They won four more games in postseason play in route to the Section VI Class B championship. They knocked off teams including: Maryvale, Clarence, Kenmore East and Williamsville South. By the way, for all of you basketball junkies out there, Willie Cauley turned out to be the father of the University of Kentucky’s and the NBA’s Willie Cauley-Stein. One of the players from the 1990-91 team revealed this to me in our talks.

Doing It A Different Way

As described earlier, other teams had gone 13-0 in the Yale Cup and went on to make deep runs in postseason play. I’m thinking about the above-mentioned Bennett High School, in addition to Burgard Vocational and Buffalo Traditional High Schools. It was probably how Coach Jones, and his 1990-91 team did it that season that was so impressive. And again, as a novice at the time I didn’t understand everything I was seeing. Researching the entire series of events years later though, it was remarkable in my opinion.

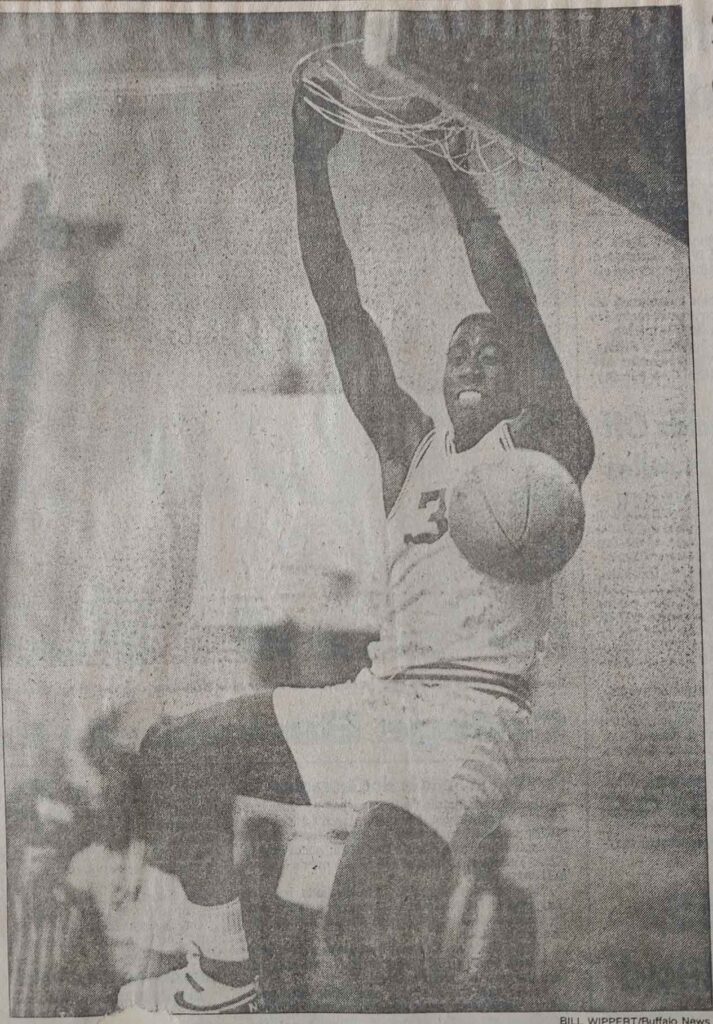

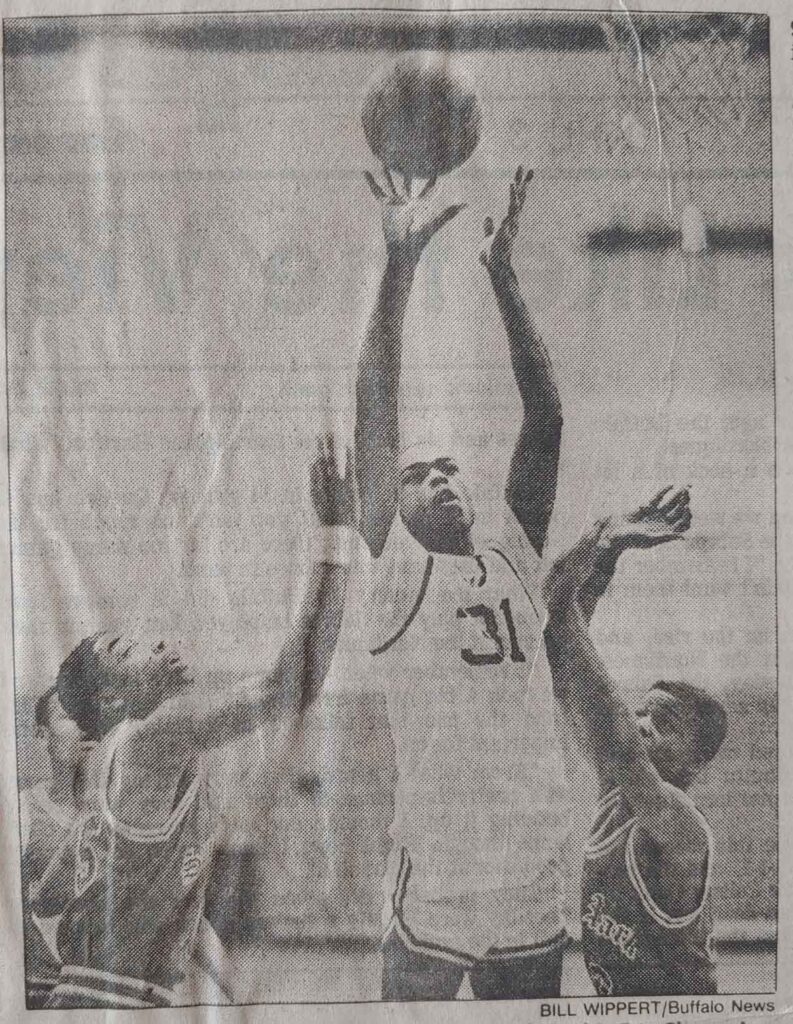

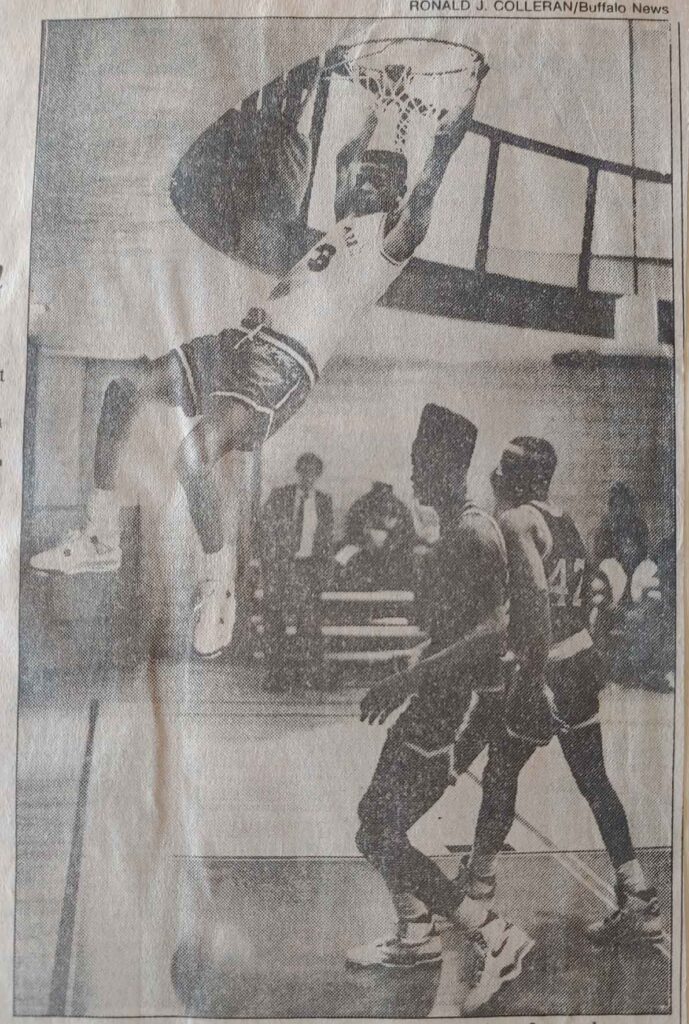

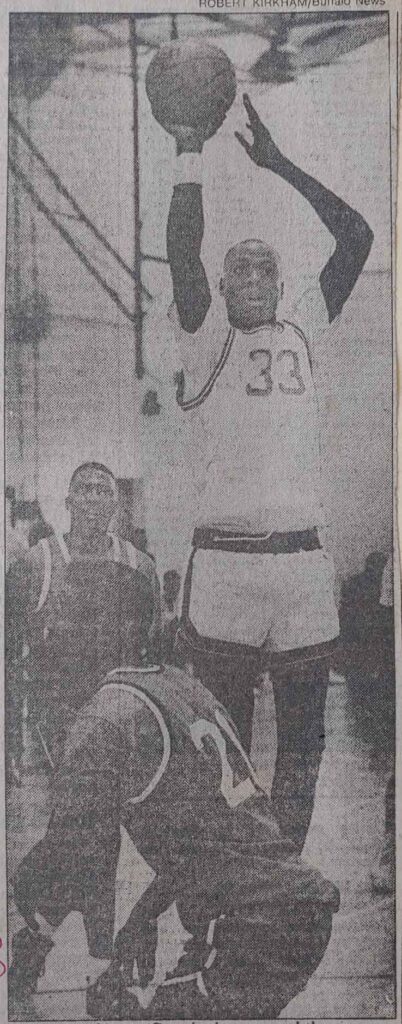

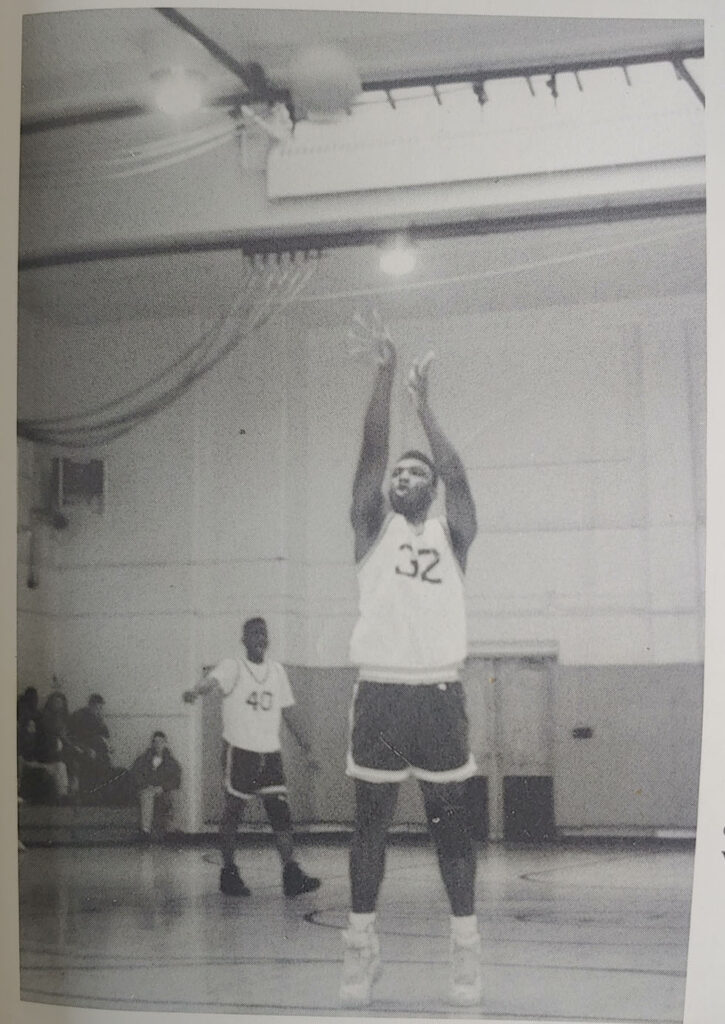

Again, most of the players on that team admitted that athletically, they were small in terms of size. Their tallest player, No. 55, Charles “Chuck” Thompson, was 6’5”. They also didn’t play a flashy style of basketball with lots of high-flying dunks and no-look passes like you would see in some of the old And1 Mixtape Tours, by players like Rafer Alston, best known as ‘Skip 2 My Lou.

A Winning Formula

Instead, they played a patient and disciplined style as described above using fundamentals, disciplined man to man team defense, methodical offensive sets and unselfishness across the board. They talked on defense, boxed out and rebounded the ball, and created an abundance of easy baskets for one another.

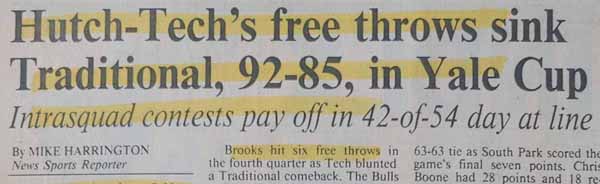

“Games are won and lost on the free throw line!” They were also a solid free throw shooting team, one of Coach Jones’ other basketball gospels. They didn’t win every game decisively and it was their free throw shooting which secured some of their close victories. Some victories required late timely baskets by No. 13, Curtis Brooks, from close range or out beyond the three-point arc. Others were due to team efforts where there were balanced point totals, assist and rebounds.

Unselfishly Putting The Puzzle Pieces Together

“Basically, it’s like I said. Everything was a piece of the puzzle. Like me for example. They used to call me the ‘Black Hole’, because they knew that if they threw the ball down to the me that I was going to shoot it! That’s the way that I was when I got the ball,” said Charles Thompson, the center for the team.

“Not everyone had that scoring mentality. I had it, Pep had it, Curt had it. Quincy was the outside three-point shooter. Everybody was learning how to play their role to get us to a point to play better,” Thompson continued. “Because after Frankie (Harris) left, it was just us there, the original people that came in that freshman year. The entire starting five, we could now work together, and we did good.”

It Wasn’t A “Star” System: No One Was Looking To Be A Star

“So that’s what his structure was. We didn’t really have – it really wasn’t like a pro-offense. It wasn’t about dumping the ball down to one person. It was like that, but it wasn’t designed for that,” Curtis Brooks said during our interview. “He (Coach Jones) never said, ‘Get the ball. I want you to SHOOT! SHOOT! SHOOT!’ He’d say, ‘Move the ball and if you’re in that area, that’s your shot!’ It wasn’t a star system!”

Of the many fascinating aspects of my discussions with Curtis Brooks, none was more fascinating than that of Coach Jones’ offensive philosophy. Still a novice and a ‘project’ at the time, I didn’t understand everything. In a nutshell, Coach Jones taught a team-oriented style of offense where no one player was featured. The focus was on moving the ball and creating good shots for everyone, especially “uncontested” layups. He also encouraged easy baskets off created turnovers.

This arguably conflicted with players who wanted to play “isolation-style” basketball which we learned by default on Buffalo’s playgrounds. It also conflicted with what I call in The Engineers, the ‘Fab Five Era’. It was the era where highly talented younger players came in and immediately demanded to play based upon their talent levels, but not necessarily embracing the coach’s culture and teachings.

A Special Group Of Players

“Jones was looking for a certain kind of kid, a coachable kid!” I could attribute this quote to a single player, but because multiple people stated it, I consider it a recurring, underlying theme. Coach Jones was in fact not looking for the most talented kids, but instead kids who would submit to his coaching and culture, and sacrifice for their teammates.

Keep in mind that this was all at our city’s lone technical high school which required an entrance exam for admittance. In writing my story, I’ve pondered that while Coach Jones knew his fundamentals and was a “true student of the game”, he also gathered a special collection of players at the right time. Interestingly, many of these players decided to attend the school before he got there (see my Kevin Roberson piece). They were coachable, driven, had good chemistry as described above, and they loved playing the game. The latter point is important because some of them went through hard times and pondered quitting but didn’t.

That said, Coach Jones gathered those players in such a way that they all grew up together in his program. They stayed together, and this created a bit of a family. It wasn’t a smooth ride for every player, but they loved each other and the game enough to persevere through the early losing they experienced. They also persevered through their knowledgeable, but at times onery coach, who admitted that if he could go back that, “I would be just as demanding, but more understanding!” He ran the entire program by himself with no regular assistants and no formal modified or junior varsity program feeding him trained up players. Again, remarkable.

“You have to be good to be lucky and lucky to be good,” Coach Jones said to his players often among other things. Arguably, there was a bit of luck and circumstance in what the 1990-91 Engineers accomplished. A bit of a ‘vacuum’ was created in the Yale Cup that 1990-91 season. Super stars like the great Ritchie Campbell and Marcus Whitfield from Burgard, Trevor Ruffin from Bennett, and Chris Williams from Buffalo Traditional had graduated. This left the championship “up for grabs” as my Uncle Jeff used to say. The next year in the 1991-92 season, the Riverside Frontiersman won the Yale Cup with a record of 11-2. The year after that, the McKinley Macks and the Seneca Indians shared the title with a similar record. The Buffalo Traditional Bulls dominated the league for the next three years.

The Difference One Team Can Make

“It was a nice chapter.” As described in the opening of this piece, Curtis Brooks, the engine who powered the 1990-91 Engineers initially felt that what they did wasn’t that big a deal. I interviewed him twice. The second time we spoke, he acknowledged that for our school at that time, it was in fact a big deal. While they were in Coach Jones’ program doing what they had been groomed to do the previous two to three years, others of us looked on in amazement. When you’re in a little fishbowl like a high school and one of your sports teams is winning in dominant fashion, it is a big deal. It also means something when you see the guys on that team up close around the hallways of the school in between classes. You can start to dream of doing it yourself.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’ve never forgotten the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech Engineers. I learned of them two to three years before getting to Hutch-Tech through my brother Amahl’s yearbooks. Once I got to the school, I wanted to be just like them. I first saw them play in their 93-90 thriller they pulled out against the Grover Cleveland “Presidents”. That day they wore their white tank tops, and their maroon and trunks. They mostly wore black sneakers like the Michael Jordan-led Chicago Bulls. Yellow ribbons were pinned into their laces in tribute to our military servicemen and women fighting in the Persian Gulf (Operation Desert Storm).

Did I accomplish that goal of being just like them? Well, I would encourage you to check out my book project once its finished. I’ll just say that it was a lot harder than it looked for a number of reasons. The 1990-91 Engineers did, however, inspire me to strive for something for the first time in my young life. They helped teach me a set of lessons that arguably carried me through the rest of my life into multiple arenas.

The Class Of 1992 Seniors: The 1990-91 Team’s Unsung Heroes

“I loved Michael Mann. His head was always in the game!” I couldn’t finish this essay without acknowledging the 1990-91 team’s unsung heroes. On any championship team, there are players in the background contributing who may not get as much recognition.

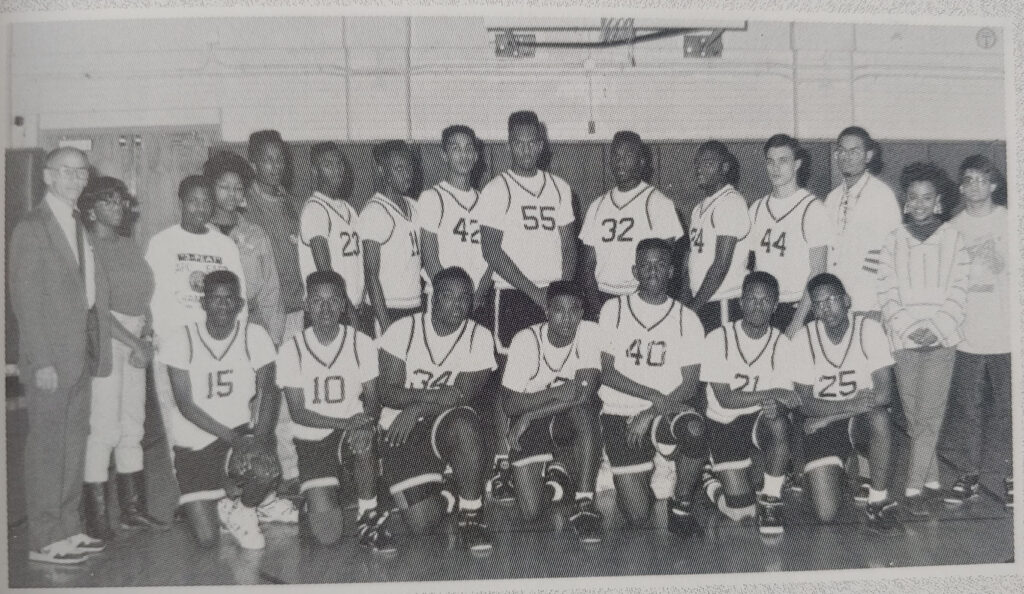

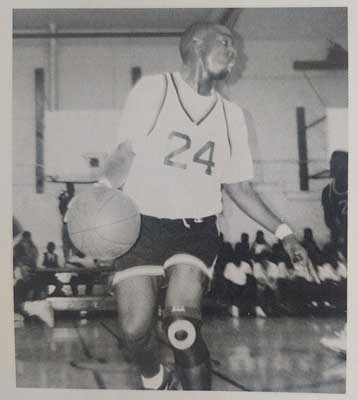

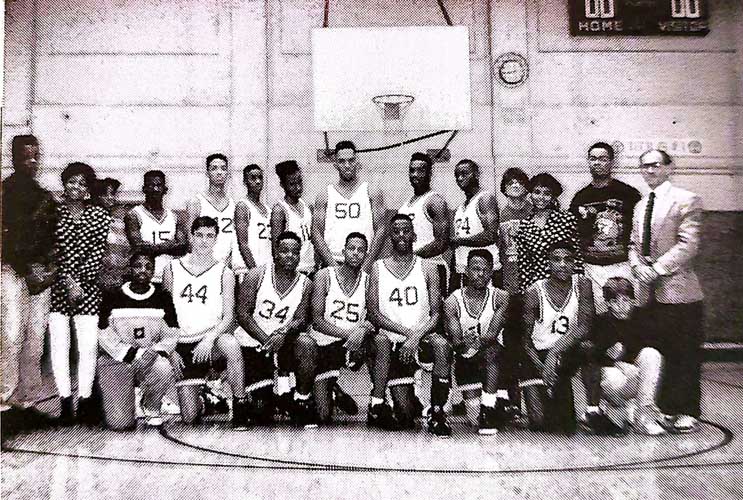

The times I saw the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team play, I observed that Coach Jones kept a ‘tight player rotation’. He typically subbed in three juniors: No. 21 Michael Mann, No. 24 Dion Frasier, and No. 44 Christain J. Souter. They had been in the program since day one when Coach Jones took it over two years earlier when they were freshman. Like the Class of 1991 seniors, they literally grew up in the program.

Michael Mann usually spelled Curtis Brooks at the point guard position albeit not for long. In our discussions Coach Jones always spoke of Michael Mann affectionately. He always noted that, “His head was always in the game even if he wasn’t on the floor.” The next year I found that he also supported his teammates even when he was sidelined by injury and unable to play. He always kept a positive attitude, something not easy to do.

Chris Souter and Dion Frasier got in to play defense and took the occasional open shots that year. The three of them were the tri-captains, the next year for the 1991-92 team, my sophomore season and first year on the team. They were arguably the last remnants of the culture Coach Jones originally established when he got to Hutch-Tech.

It Was The Culture

“It was the culture. Jones set the culture,” Pep Skillon said discussing the basketball program Coach Jones created at our school. In hindsight it was a mini-college program. One of the main pillars of that culture was perseverance. That is staying focused and hopeful during adverse stretches. The 1991-92 team likewise experienced struggles that the 1990-91 did not. Somehow though, it rebounded for a deep sectional run of its own. In my opinion, this was due in large part the above-mentioned tri-captains, and things weren’t the same once they graduated.

“That was a great feeling being around a group of guys who played together and really like being around each other. Those guys were great. They were great teammates as well as great guys off the court – a very close-knit group (the 1990-91 team). They were friends as well as teammates.” The second opening excerpt for this piece is from No. 23 Adonis Coble who played on both teams. He was also a member of the Class of 1992. His words expressed the importance the culture of that 1990-91 team. He led our 1991-92 team in his own way during some difficult stretches the next year.

Their Final Game: The 1991 Far West Regional

The 1990-91 team’s final game was a lopsided loss to the Newark “Reds” from the Rochester area. It was the 1991 Class B Far West Regional or the Super-Sectional. There the winner earned a trip to Glens Falls. The Reds were a physically bigger, stronger and more experienced team. They defeated the Kensington Knights also from the Yale Cup in the same game the previous year.

As often is the case in sports, there are multiple explanations for what happened. There were rumors of the core the 1990-91 team staying out late the night before the game. My research revealed that this wasn’t altogether true. It further revealed that the team was late getting to Rochester’s War Memorial Stadium. There was an accident on the I-90 expressway. They started changing on the bus and got to the arena with little time before tipoff to settle in before the challenge at hand. It was a loss that Coach Jones lamented until his last days.

How Would They Have Fared Against The Dominant Buffalo Traditional Teams?

One of the most fun (and nerve-wrecking) parts of sports is speculating on matchups that we’ll never see. In the movie Rocky Balboa, there’s a scene where a sports network simulates Rocky matching up with the current much younger champion, Mason “The Line” Dixon. The computer likewise predicts Rocky knocking out the younger fighter, setting up the movie’s plot. Likewise, we speculate on how Mike Tyson would’ve fared against Muhammad Ali. We speculate on how players like LeBron James and Stephen Curry and their teams would’ve fared in the 1980s NBA when the game was more physical. We speculate on how today’s NFL champions would’ve fared against the more physical 1980s and 90s teams.

I’ve likewise wondered how the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team would’ve matched up with the above-mentioned legendary Damien Foster– and Jason Rowe-led Buffalo Traditional teams which dominated the Yale Cup from 1993 to 1996 (and other notable Yale Cup champions). The Bulls were athletic, tall, and highly skilled. Most of their players could shoot the ball from long-range and they eventually made two trips to Glens Falls, winning the federation championship the second time. It would’ve been an interesting matchup as the 1990-91 Engineers had a level of athleticism and physicality of their own. They were fundamentally sound though on both ends of the court. Many would give the advantage to Coach Joe Cardinal’s Bulls, but I predict the 1990-91 Engineers would’ve been a formidable foe for them.

The Players Who Contributed To That Season But Graduated

The Damien Foster– and Jason Rowe-led Buffalo Traditional teams seemed to instantly ascend as champions. In contrast the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team gradually built up to that point. As described, there were numerous lumps along the way leading up to that season. For many teams that evolve to become champions, there are often players who contribute along the way who don’t ultimately get to hoist the championship trophies.

For the 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team there was Adrian Brice of the Class of 1989. The lone senior on the 1988-89 team, he played point guard the year Coach Jones took over the program. He came up in numerous interviews, and his nickname was “Flash”. From the Class of 1990, there was Ed Lenard, Jerome Freeman, Frankie Harris, Derrick Herbert and Michael Brundige. One of Coach Jones’ favorite stories to tell us was that of Frankie Harris passing up uncontested layups. He embellished the story for humor, and used it as a teaching tool.

Closing Thoughts On The 1990-91 Engineers

“Curt Brooks’ work ethic was unbelievable. He would wear a weighted flap jacket during basketball practice. Although he was ‘the star’, he didn’t slack off during practice, or during the games,” said Jermaine Fuller, one of two sophomores on the 1990-91 team. His words reflect the lasting impression No. 13, Curtis Brooks made, and it reminds me of a quote that Brooks shared with me that Coach Jones told them all the time. That quote said, “Every person can make a difference, and everyone should try!”

I also want to acknowledge the other players on the team that I didn’t mention. In the book, the names are changed for those who didn’t agree to be a part of this work. For historical completeness however, I want to mention the other guys here. They are Jason Parrish and Juno Patterson both from the Class of 1992. There was also Andre Huggins from the Class of 1993. The 1990-91 Hutch-Tech boys’ basketball team was very close to Coach Jones’ ideal make up of a team. This consisted of five seniors, five juniors and two sophomores.

I’ll divulge that it’s a rule that he bent his final two years at Hutch-Tech. To learn about that and how those of us who tried to continue what the 1990-91 team’s success fared, you’ll have to read The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story. I’ll just say that it turned out to be a lot harder than it looked for everyone. And again, there were a number of reasons for that.

I spoke of Coach Jones numerous times throughout this piece. If you want to learn some more about him and his importance my story and my life, take a look at the at the video below from my sports YouTube channel. If you watch it, please give it a like and leave a comment.

Acknowledgements And Final Words

The opening quote for this piece is from the above-mentioned Pep Skillon, which I think underscores a major theme of this account, unselfishness. I want to acknowledge a lot of people without whom this essay (and others) would not have been possible. Thank you to the players and coaches I interviewed. There is also Coach Jones and the Jones family. Finally, I’d like to acknowledge all the team managers who were critical parts of the basketball program during those years.

I also want to acknowledge Laura Lama from my Class of 1994. The second picture of the 1990-91 Engineers as a team is from our 1991-92 yearbook the next year, which Laura kindly shared with me. There was a back forth to get the image just right, and she had more important matters to deal with at the time. It’s missing one player, but it was always one of my favorite pictures of the team. You can see the old and antiquated gym we played in which no longer exists. Finally, I want to thank the previously mentioned Michael Mann for the visual of his gold jacket he shared from the 1990-91 team’s championship season.

Thank you for reading this piece. I intend to create more promotional/teaser pieces for The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story. These will be both via print and video as I journey through the final steps of the book’s completion. As described, I created a page here on Big Words Authors for the purpose of giving a background of the book and grouping all the promotional pieces such as this in one place for interested readers.

On my first blogging platform, the Big Words Blog Site, there are interviews of some of the most accomplished Section VI players from my era including: Jason Rowe, Tim Winn, Carlos Bradberry and Damien Foster. I also interviewed legendary LaSalle Head Basketball Coach, Pat Monti. Finally, there are several other basketball-related essays related to my book project. If you liked this piece, please share it on your social media and leave a comment beneath this piece.

The Big Words LLC Newsletter

For the next phase of my writing journey, I’m starting a monthly newsletter. I will be for my writing and video content creation company, the Big Words LLC. I plan to share numerous things. They include inspirational words, pieces from this blog and my first blog, and select videos from my four YouTube channels. Finally, I will share updates for my book project The Engineers: A Western New York Basketball Story. I promise to protect your personal information and privacy. Click this link and register using the sign-up button at the bottom of the announcement. You can also email me bwllcnl@gmail.com to subscribe. Regards.